LSD is famous (and infamous) for its potent hallucinogenic effects – not exactly something you’d think to give to a person with schizophrenia. In fact, hallucinogens like LSD can trigger or worsen psychosis, so they’ve been strictly off-limits in treating psychotic disorders. However, a groundbreaking scientific breakthrough is turning that notion on its head. Researchers have modified the LSD molecule to create a new compound that retains LSD’s therapeutic potential (promoting brain growth and resilience) while drastically reducing its hallucinatory effects. This modified LSD analogue – currently nicknamed JRT – is showing promise as a treatment for schizophrenia’s hardest-to-treat aspects, without causing a psychedelic trip. In this blog, we’ll dive into how scientists achieved this molecular feat, what early studies indicate about its benefits, and what it could mean for future schizophrenia therapy.

Why modify LSD for schizophrenia?

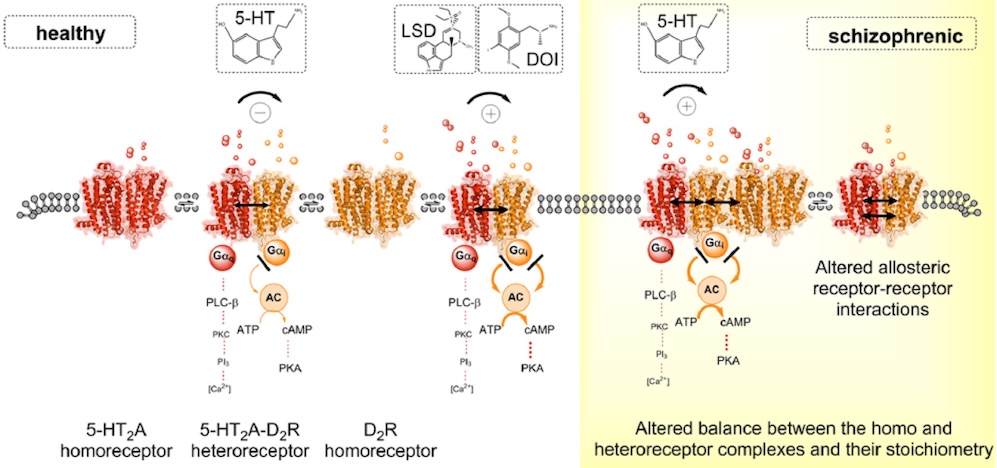

Schizophrenia is a chronic psychiatric disorder often marked by hallucinations and delusions (positive symptoms), but equally debilitating are its negative symptoms (like apathy and social withdrawal) and cognitive impairments. Current antipsychotic medications mostly target the positive symptoms (reducing hallucinations/delusions) and often have substantial side effects. Meanwhile, negative symptoms and cognitive deficits remain difficult to treat – patients may continue to struggle with flattened emotions, lack of pleasure (anhedonia), and memory or attention problems.

Interestingly, psychedelics like LSD interact with serotonin receptors and promote neuroplasticity (growth and connectivity of brain cells), which could potentially help with mood and cognitive function. But, of course, giving full-fledged LSD to someone with schizophrenia is out of the question due to safety – it could massively exacerbate psychosis. “No one really wants to give a hallucinogenic molecule like LSD to a patient with schizophrenia,” notes Dr. David Olson, a leading researcher in this field. The challenge has been: can we separate LSD’s therapeutic properties from its hallucinatory properties? If yes, we might harness the good (neuroplasticity, anti-depressant effects) without the bad (sensory distortions, paranoia). This is exactly what Olson’s team aimed to do.

The making of a non-hallucinogenic LSD analogue (JRT)

At the University of California, Davis, Dr. Olson and colleagues embarked on molecular tinkering with LSD. By flipping the position of just two atoms in the LSD molecule, they created a new analogue called JRT. It’s akin to performing a “tire rotation” on the molecule, Olson quipped – a small structural change, but one that had big effects. This tiny chemical flip significantly reduced the compound’s ability to cause hallucinations while preserving – even enhancing – its pro-therapeutic actions.

JRT is chemically very close to LSD (it has the same molecular weight and a very similar shape). However, its pharmacological profile is distinct. Notably:

- JRT is highly selective for certain serotonin receptors (5-HT2A in particular). LSD also hits 5-HT2A strongly (that’s largely responsible for hallucinations), but LSD hits many other receptors too. JRT’s tweak improved its selectivity, meaning it more precisely targets the receptor pathways linked to therapeutic benefit (like neuron growth) and less so those causing sensory disruptions.

- JRT did not produce hallucinogenic behaviors in mice. Scientists have ways to tell if a mouse is “tripping” (one common sign is a head-twitch response in rodents when 5-HT2A is overstimulated). When they gave mice JRT, the usual LSD-induced head-twitch was vastly diminished, indicating the drug is far less hallucinogenic.

- JRT retained powerful neuroplastic and psychotropic benefits: In cell and animal studies, JRT spurred significant neuronal growth. Treated neurons grew more branches (dendrites) and formed more synaptic connections – a 46% increase in dendritic spines and 18% increase in synapses in one experiment, which is remarkable. This kind of growth is associated with better brain network function and resilience, something potentially beneficial in neuropsychiatric disorders where certain brain circuits have atrophied or become under-connected.

- JRT didn’t trigger schizophrenia-related gene expression. High-dose LSD tends to ramp up expression of genes linked to psychosis (which is one reason it’s risky in schizophrenia). JRT, by contrast, did not promote those gene changes. It appears to avoid molecular pathways that would worsen schizophrenia.

- JRT acted as a potent antidepressant in animals. Intriguingly, tests showed JRT had an antidepressant-like effect about 100 times more potent than ketamine (ketamine is a fast-acting antidepressant). This suggests JRT’s neuroplastic boost strongly translates into mood improvement potential.

- JRT improved cognitive flexibility in animal models. Mice with deficits in reversal learning (a cognitive task linked to the kind of executive function impairments seen in schizophrenia) performed better when given JRT. This hints that the compound could help with cognitive symptoms, not just mood or negative symptoms.

Dr. Olson was understandably excited by these findings. “JRT has extremely high therapeutic potential. We’re now testing it in other disease models, improving its synthesis, and creating new analogues of JRT that might be even better,” he said. The creation process was arduous – it took nearly five years and a 12-step chemical synthesis to make enough JRT for testing – but the payoff is a first-of-its-kind drug. Olson emphasizes, “The development of JRT demonstrates that we can use psychedelics like LSD as starting points to make better medicines. We may be able to create medications that can be used in patient populations where psychedelic use is precluded.” In other words, if you can remove the hallucinatory aspect, you open the door to using psychedelic-inspired drugs for illnesses like schizophrenia, where giving someone a hallucination would normally be a non-starter.

Implications for schizophrenia treatment

While JRT is still in the research phase (so far tested in vitro and in mice), the implications are exciting. For schizophrenia, the big hope is addressing negative and cognitive symptoms, which, as mentioned, are areas of huge unmet need. Olson specifically notes that JRT could help with things like anhedonia (inability to feel pleasure) and cognitive function – domains where standard antipsychotics have little effect. In the mouse studies modeling some aspects of schizophrenia, JRT improved measures related to these domains (like the cognitive flexibility test mentioned).

Imagine a medication derived from LSD that doesn’t make you hallucinate, but does help rebuild synaptic connections in your prefrontal cortex. That could potentially improve motivation, social engagement, and memory in patients with schizophrenia – improving quality of life and functional outcomes. Importantly, it could do so without adding to psychosis. The fact that JRT did not exacerbate (and even suppressed) gene expression patterns tied to psychosis in the experiments is a reassuring sign.

It’s also notable that JRT’s antidepressant potency might make it useful for the depression that often accompanies schizophrenia. Many patients suffer from depressive symptoms or high levels of apathy. A drug that boosts neuroplasticity could potentially lift mood and cognitive fog concurrently.

Another implication is for other conditions involving synaptic loss and brain atrophy. The researchers specifically mention exploring JRT in neurodegenerative diseases as well. For example, could a similar compound help in Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s (where you’d want to promote neuron growth but certainly don’t want hallucinations)? It’s a tantalizing prospect that goes beyond schizophrenia.

Expert reactions and next steps

The development of JRT has generated buzz in the neuropsychopharmacology world. It provides a proof-of-concept that non-hallucinogenic psychedelics (“psychoplastogens”) are possible – something that has been theorized for a while. In plain terms, it means scientists might create medications that give you the brain-healing benefits of a psychedelic without making you trip. This could vastly widen the clinical applicability of psychedelic-based treatments. As one science writer put it, it’s like “harnessing LSD’s therapeutic power with reduced hallucinogenic potential”.

For schizophrenia patients and clinicians, cautious optimism is warranted. It will take time (and likely more tweaking) before a drug like JRT reaches clinical trials in humans. The compound will need further testing for safety, efficacy, and off-target effects. But early data is promising enough that Olson’s team is pushing forward. They are refining JRT’s synthesis to produce it more efficiently and even making new analogues based on JRT’s structure to see if they can improve the profile further.

One remarkable aspect of this research is how it exemplifies modern medicinal chemistry meeting psychedelic science. The idea that a simple atomic rearrangement could strip LSD of its “psychedelic trip” while keeping its “neuroplastic kick” is almost poetic. It reminds us that the difference between a drug and a medicine can be just a couple of atoms. As Olson analogized, it was like rotating the tires on a car – everything looks the same, but performance changes.

If and when JRT or a similar compound enters human trials, researchers will be watching closely for whether it indeed helps cognitive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia patients. If it does, it could usher in an entirely new class of treatments. And not just for schizophrenia: other psychiatric conditions characterized by synaptic loss (chronic stress disorders, PTSD, etc.) or even neurodegenerative illnesses might benefit from psychoplastogens that don’t cause perceptual disturbances.

Conclusion

The journey of LSD from 1960s counterculture to 2020s cutting-edge medicine has taken an intriguing turn. By cleverly tweaking the LSD molecule, scientists have created “LSD-lite” (JRT) – a compound that heals the brain like a psychedelic but spares the mind from hallucinations. Early studies show it can promote neuron growth, act as a potent antidepressant, and improve cognitive deficits in models of schizophrenia, all without triggering the behaviors associated with an LSD trip. This scientific feat opens the door to treating illnesses like schizophrenia in a novel way, offering hope for tackling symptoms that current drugs leave largely untouched (such as anhedonia and cognitive impairment).

While there’s a long road ahead before treatments like JRT become available, the concept is a game-changer. It suggests we don’t necessarily need the subjective psychedelic experience for objective healing to occur – a notion that could make psychedelic-inspired therapies palatable to a much wider patient population. For individuals with schizophrenia and their families, this research offers a glimpse of a future where the therapeutic power of psychedelics can be harnessed safely, turning a once-taboo drug into a source of healing. As Dr. Olson said, “We may be able to create medications that can be used in patient populations where psychedelic use is precluded.” In short, LSD’s rebel cousin JRT might just show that you can teach an old drug new tricks, to the great benefit of those who need it most.

Sources: UC Davis news release on the LSD analogue discovery

ucdavis.eduucdavis.edu;

Published findings in PNAS summarizing JRT’s properties

ucdavis.eduucdavis.edu;

Expert commentary from Dr. David Olson

ucdavis.eduucdavis.edu.